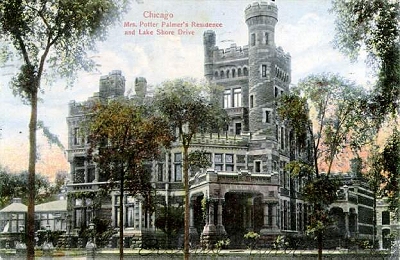

The Chicago mansion of Potter and Bertha Palmer, on North Lake Shore Drive.

Built in 1885, it was torn down in 1950. Critics called it "the castle plucked from a

goldfish bowl."

|

|

Mrs. Palmer and the roots of a legacy

By Harold Bubil. Sarasota Herald Tribune. Published: Sunday, January 17, 2010

'KEEP UP with the procession, is my motto, and head it if you can. I do head it. And I

feel that I am where I belong."

That quote, said author Sally Sexton Kalmbach in a presentation last week to the

Historical Society of Sarasota County, is attributed to Bertha Palmer, whose remarkable

life and dramatic impact on Sarasota history and real estate development, is being

celebrated in the Bertha Palmer 2010 Sarasota Centennial. |

Long before she arrived Sarasota on Feb. 10, 1910, Bertha Honor Palmer was one of the

most famous women in America, hailed as a social leader and a champion of women's causes

and labor fairness.

She was born in Louisville, Ky., in 1849, and lived in the "Kentucky Colony" on

Ashland Avenue after her family moved to Chicago, said Kalmbach, who has written a book

titled "The Jewel of the Gold Coast: Mrs. Potter Palmer's Chicago" (Ampersand

Inc., 2009). The oldest of six children, she was very close to her father, H.H. Honor ,

who taught her about business and real estate during her youth.

She was sent to finishing school in Washington, D.C., learning to become a gracious and

skilled hostess. When she was 13, she met Potter Palmer, a 36-year-old businessman who

developed the use of credit and merchandise exchange called the Palmer System. He built

the premier dry-goods business in the city, making shopping a pleasurable pastime, and

sold interests in it to Marshall Field and Levi Leiter in 1865. It became Marshall Field

and Co.

Palmer was so impressed with the confident, poised teenager that he decided to wait for

her to become old enough for a marriage proposal. Their wedding was in 1870, when she was

21 and he was 44. That the father of the bride was in debt to the groom did not make this

a mercenary union; Potter and Bertha enjoyed a long, happy and prosperous marriage.

They lived in the new and opulent Palmer House hotel, a $3.5 million "wedding

gift" that burned down in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, along with dozens of other

buildings owned by Potter Palmer. Based on his personal reputation, Potter secured an

enormous loan to rebuild his empire, including a bigger and better Palmer House. He

recovered from the fire to become Chicago's biggest landowner.

In Potter Palmer's 1902 New York Times obituary, he was credited with rebuilding Chicago

after the great fire, even though he seriously considered leaving reconstruction to others

and moving out of the city. His wife told him, "Mr. Palmer, it is the duty of every

Chicagoan to stay here and devote his fortune and energies to rebuilding this stricken

city."

In the meantime, Bertha Palmer, also known as Cissie, was not the retiring wife. In early

evening conversations with her much-older husband, she learned even more about business

and real estate. In 1874, she gave birth to their son, Honor -- a name that will sound

familiar to those who drive the streets of east Sarasota. Their second son was Potter Jr.

When Bertha's sister, Ida, married President U.S. Grant's son, the socially skilled Bertha

planned the lavish wedding. She also arranged the 1899 marriage, at the Palmer home in

Newport, R.I., of her niece, Julia Dent Grant, to the Russian Prince Cantacuzene. (Prince

and princess fled Russia after the revolution of 1917 and eventually settled in Sarasota,

where the prince became a vice president of the Palmer Bank.)

By 1885, the Palmers had moved out of Palmer House and built an enormous mansion on North

Lake Shore Drive. It could best be described as Eclectic Revival. The architect borrowed

from many different styles. It soon became known as "the monstrosity" and

"the castle plucked from a goldfish bowl," said Kalmbach. The house, which was

torn down in 1950 to make way for two high-rises, had no exterior doorknobs. If you wanted

to get in, you had to wait for a servant to let you in, but only after you mailed a letter

seeking an appointment with the lady of the house.

And what a lady she was. In 1890, when a woman's place was firmly in the home, she became

president of the Board of Lady Managers of the 1892-93 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In

this role, she traveled the country and Europe to promote the fair. Her New York Times

obituary, published May 7, 1918, notes that she established lasting friendships with the

queens of Italy and Belgium, as well as Belgium's Prince Albert. In the 1900s, she

befriended England's King Edward VII, who often visited her home in London. She had

another in Paris.

She received a medal from the French Legion of Honor when she was the lone female on the

National Commission to the Paris Exposition in 1900 -- even though the French objected to

her appointment by President McKinley.

She organized the Charity Ball in Chicago each year, a highlight of her philanthropic

activities. A "patron of the arts and labor," as the Times reported, she built a

large addition to the Palmers' North Lake Shore Drive mansion for the display of her large

collection of art. She is credited with introducing French impressionist art to America at

a time when it was ridiculed in France, said Kalmbach.

"Mrs. Palmer had always a warm spot in her heart of working people of every class,

and helped them from time to time without a hint of condescension or charity," said

the Times obituary. "At one time, she turned her house over to a reception of

shopgirls. She was tireless in devising plans for aiding factory girls and became a patron

of the Women's Trade Union League. ... She spent $50,000 each year in charity, sending the

amount anonymously."

A supporter of women's equal pay for equal work, her dignity and grace extended to

relations with her Sarasota employees.

"She did not look down on people who were working for her," said Hope Black,

history advisor to the Bertha Palmer Centennial celebration. "It was once mentioned

that she could be very snooty to people within her socioeconomic area. People thought she

could be high and mighty sometimes, but when she was talking to her working people, she

was very kind, and joked with them. They weren't afraid of talking with her."

In his will, Potter Palmer left the bulk of his estate to Bertha. His advisors objected,

fearing the young woman would soon find a new husband. Replied Potter, "If she does,

he will need the money." She didn't.

Bertha Palmer's death at her Sarasota home, The Oaks, in 1918, just short of her 69th

birthday, was reported to be caused by pneumonia. But Black and others now believe she

suffered from breast cancer. She and her husband are buried in Chicago's Graceland

Cemetery. Kalmbach quoted the words of one obituary writer: "There can be no sorrow

at the end of such a journey."

ringlingdocents.org

|